Discrete Extremal Quasiconformal Maps

Exploration & Experiments at TU Berlin (July 2023)

The Grötzsch Problem

Suppose we have two rectangles with different aspect ratios. There is no conformal map between them which sends each vertex of one rectangle to the corresponding vertex of the other rectangle. But we can look for a map which is "as close to conformal as possible". To do so, we define the dilatation of $f$ at a point $p$ as the ratio of the singular values of $df$ at $p$. We say that the dilatation of $f$ is the maximum dilatation at any point $p$ of the domain. A mapping is called $K$-quasiconformal if this maximum dilatation is at most $K$. Note that a $1$-quasiconformal map is conformal. An extremal quasiconformal map is a map between two domains with minimal dilatation. If the domains are conformally equivalent then this extremal map will be a conformal map, but in general it will be a quasiconformal map with some dilatation $K > 1$.

Back to the example of two rectangles, we can map between them using an affine map, which stretches the $x$-axis by $\tfrac{a'}a$ and stretches the $y$-axis by $\tfrac{b'}b$. Without loss of generality, suppose that $\tfrac{a'}a > \tfrac{b'}b$; then this mapping has dilatation $\tfrac{a' b}{a b'}$. Grötzsch proved that this dilatation is optimal: the extremal quasiconformal map between two rectangles is the affine map which stretches one onto the other.

Finally, note that dilatation is conformally-invariant: if we compose $f$ with a conformal map on either side, the ratio of its singular values will not change. Hence, if we have two domains which are conformally-equivalent to these rectangles and we ask for the optimal mapping between them, the result will be decomposable into a conformal map, followed by an affine map, followed by another conformal map. And the dilatation will be the same at all points.

Further reading: Lectures on Quasiconformal Mappings by Ahlfors, On five papers by Herbert Grötzch by Alberge & Papadopoulos, this math.stackexchange question.

Measuring Discrete Distortion

If we have two triangles, we can always map between them using an affine map. If the first triangle has edge lengths $\ell_i$ and the second has edge lengths $\tilde \ell_i$, then the distortion is given by: \[ \text{distortion} = \frac{\left(\ell^2\right)^T \!\!\! A \tilde \ell^2}{\sqrt{\left(\ell^2\right)^T \!\!\! A\, \ell^2}\sqrt{\left(\tilde \ell^2\right)^T \!\!\! A \tilde \ell^2}} \] \[ A = \frac 12 \begin{pmatrix}-1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & -1 & 1\\ 1 & 1 & -1\end{pmatrix}, \] where $\ell^2$ denotes the vector $(\ell_0^2, \ell_1^2, \ell_2^2)^T$.

Using Heron's formula, one can show that the quantity $\left(\ell^2\right)^T \!\!\! A \ell^2$ equals a constant times the squared area of the the triangle, and is nonnegative if and only if the edge lengths satisfy the triangle inequality.

In this notation, the cotangents of the triangle corner angles can be expressed as \[ \begin{pmatrix} \cot \alpha_0 \\ \cot \alpha_1 \\ \cot\alpha_2 \end{pmatrix} = \frac {A^{-1}\ell^2} {\sqrt{\left(\tilde \ell^2\right)^T \!\!\! A \tilde \ell^2}}, \] \[ A^{-1} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}, \] (which can be derived using the law of cosines, the sine formula for area, and the definition that $\cot \alpha = \tfrac{\cos\alpha}{\sin\alpha}$.)

We can hence re-express the distortion formula in terms of cotangents: \[ \text{distortion} = \begin{pmatrix} \cot \alpha_0\\\cot\alpha_1\\\cot\alpha_2\end{pmatrix}^T A^{-1} \begin{pmatrix} \cot \tilde\alpha_0\\\cot\tilde\alpha_1\\\cot\tilde\alpha_2\end{pmatrix} \]

There are also connections to hyperbolic geometry. If we scale both triangles so that the bottom side has length zero, and then align them both on the x axis, then the distortion of the affine map between triangles is given by the distance between the vertices in the halfspace model of the hyeprbolic plane.

A derivation of the cotan formula for distortion, courtesy of Boris Springborn, can be found here, and connections to hyperbolic geometry are discussed, e.g., in p.11 of Joshua Bowman's PhD thesis with John H. Hubbard.

Optimizing Discrete Distortion

Now, suppose we have two pairs of triangles and want to find an "optimal" map between them. For simplicity, we will optimize within the space of continuous, piecewise-projective maps. So if the two triangle pairs are discretely conformally equivalent, we want to recover the discrete conformal map between them. But in general, we will find some other projective map which is not a discrete conformal equivalence. Just as in the smooth case, we may hope that the optimal map between them is a discrete conformal map, followed by an affine map, followed by a discrete conformal map. To push ourselves in the right direction, we can consider maps expressed as a discrete conformal map, followed by a piecewise-affine map on each of the triangles, followed by another discrete conformal map, and define the "discrete dilatation" of this composition to be the maximum distortion of this middle piecewise-affine map. Then, we might hope that the optimal maps of this form have affine maps in the center which agree across both triangles.

It turns out that discretely conformally mapping each triangle pair to a rectangle and then applying an affine map to the rectangle does indeed yield the least possible distortion. Unfortunately, there is a whole one-parameter family of optimal maps, and most do use the same affine map across both triangles.

To see why, first suppose that we fix scale factors on the two middle vertices of each quad so that each diagonal has length 1. Then, as before, we can place these diagonals on the unit interval and embed the upper triangles into the upper halfspace model of the hyperbolic plane. By varying the scale factors of the top vertices, we can move each top vertex along a semicircle orthogonal to the real axis. It turns out that the shortest distance between these two semicircles is achieved when both vertices lie on the semicircle connecting 0 and 1. Consequently, the opposite corner angles of the quad must be right angles. The same argument shows that the lower vertices must lie on the lower semicircle as well. So both quads must be inscribed in the circle.

Now, we just need to find the pair of circle-inscribed quads with minimum (halfspace) distance between their corresponding vertices. Essentially by symmetry, one optimal solution is to embed both quads as rectangles. But applying any Möbius transformation fixing the disk and the real axis leaves the hyperbolic distance between the top vertices and the distance between the bottom vertices unchanged. So starting from this symmetric configuration, where the map really is one affine map defined on both triangles, we can deform the solution to get a 1-parameter family of optimizers which are no longer symmetric and have different affine maps on the two triangles.

We briefly explored how the triangle circumcircles get mapped to ellipses by these projective maps, but didn't find anything conclusive.

Linear Distortion Measurements

optimal projective interpolation

optimal projective interpolation

affine interpolation

affine interpolation

Rather than trying to measure the distortion of our piecewise-projective map directly, we can also try to measure the extent to which our map fails to be a discrete conformal equivalence. In general, our piecewise-projective map will associate a scale factor $u_i$ to each vertex $i$, but these scale factors will not describe the change in edge lengths between the two meshes. In a discrete conformal equivalence, the original log lengths $\lambda_{\ij} := 2 \log \ell_{\ij}$ and the rescaled log lengths $\tilde\lambda_{\ij} := 2 \log\tilde\ell_{\ij}$ differ by the sum of vertex scale factors $u_i + u_j$. Hence, we can measure the failure of our piecewise-projective map to be a discrete conformal equivalence as \[ \mathcal{E}_{\text{edge}}(u) := \max_{\text{edge}\;\ij} |\tilde\lambda_{\ij} - \lambda_{\ij} - u_i - u_j|. \]

Similarly, in a discrete conformal equivalence the logarithmic scale factor at a vertex $i$ is given by the value \[ \hat u_i^{jk} = \tilde\lambda_{\ij} + \tilde\lambda_{ki} - \tilde\lambda_{jk} - \lambda_{\ij} - \lambda_{ki} + \lambda_{jk} \] evaluated at any corner incident on $i$, and so we can also measure the failure of our piecewise-projective map to be a discrete conformal equivalence as \[ \mathcal{E}_{\text{vertex}}(u) := \max_{\text{corner}\;ijk} | u_i - \hat u_i^{jk} |. \] This vertex-based distortion measurement ends up being entirely local: the log lengths determine a target $u$ value at each corner, and then each vertex just tries to minimize the maximum deviation from any of its incident corner values. Unfortunately, it does not even necessarily yield affine maps (i.e. constant $u$ values) when squashing rectangles.

On the other hand, optimizing the edge-based distortion measurement requires solving a global problem. We can formulate this optimization as a linear program: \[ \begin{aligned} \min_{m, u_i}\; &m \quad \text{ s.t. } \\ &-m \leq |\tilde\lambda_{\ij} - \lambda_{\ij} - u_i - u_j| \leq m \; \forall\; \text{edges}\;\ij. \end{aligned} \] Interestingly, this linear program generally seems to have many optimal solutions. We can try to pick out a good one by minimizing $\max_{\ij} |u_i - u_j|$ over this optimal face. This can be done efficiently by adding constraints \[ a \leq u_i \leq b \; \forall \; i,\] and minimizing $b-a$ as a secondary objective.

On highly regular meshes, this optimal projective interpolation can yield visually-smoother results than standard linear interpolation. However, on irregular meshes it often looks worse, and does not necessarily yield an affine map when applied to stretched rectangles.

Back to a Nonlinear Theory

Rather than thinking only about projective maps, we can also consider metric distortion more generally. The space of metrics on a triangle mesh, parameterized by log lengths $\lambda$, looks like $\mathbb{R}^E$. Each conformal class appears as an affine subspace, since conformal deformations change lengths $\lambda_{\ij}$ to $\tilde \lambda_{\ij} = \lambda_{\ij} + u_i + u_j$. Now, suppose we start with some metric $\lambda$, and continuously deform it to another metric $\tilde \lambda$ in a different conformal class. If each of these deformations along the way is an extremal quasiconformal map—e.g. if we are stretching out a rectangle—then this trajectory should be orthogonal to the conformal classes in some sense. The trajectory is not orthogonal with respect to the standard metric on $\mathbb{R}^E$, but it is interesting to ask whether one can find some other inner product on $\mathbb{R}^E$ which gives us the orthogonality that we seek.

Some natural candidates include circumcentric edge diamond areas, or cotan weights, which correspond to the derivative of total area with respect to logarithmic edge lengths or squared edge lengths respectively (see §2.4 of Hana Kouřimská's thesis for discussion of the logarithmic case).

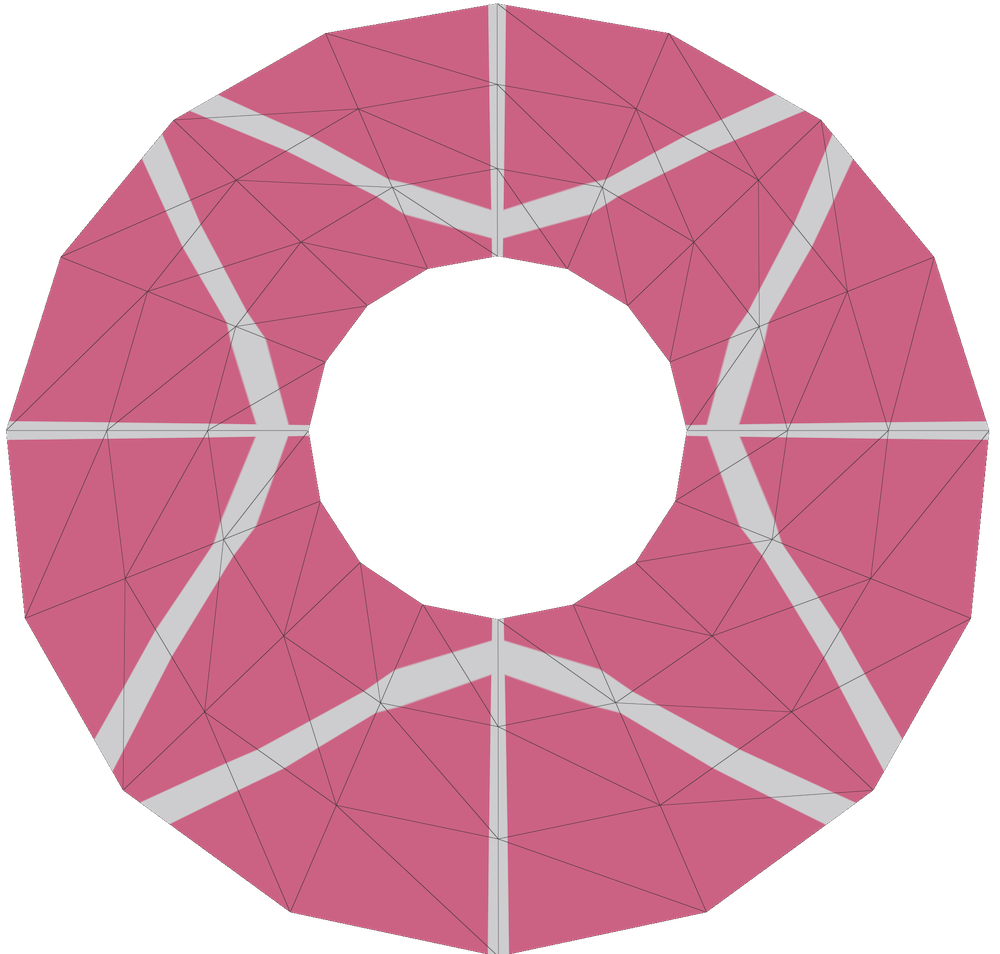

It is not immediately clear whether neither option really makes sense as a metric on the space of metrics. Instead, we can consider stretching out a small quadrilateral and try to find a metric which mackes this stretching orthogonal to our conformal classes. For simplicity, we begin with a flat torus whose edge vectors are given by $v_0, v_1$ and $v_2 = v_0 - v_1$. The linear deformations of the torus can be divided into infinitesimal conformal maps \[ \begin{pmatrix} a & -b \\ b & a \end{pmatrix},\] and their (Frobenius) orthogonal complement \[ \begin{pmatrix} c & d \\ d & -c \end{pmatrix}.\] We seek weights on the edges which make these complementary maps orthogonal to discrete conformal maps in the space of metrics on thhis flat torus. It turns out that this condition determines the weights uniquely up to scale: the weight on edge $i$ is given by $\sin (2\,\alpha_i)$. These weights are all positive as long as the angles are all acute, which is also the Delaunay condition on this flat torus.